SIAFU – THE TIM BAILY STORY

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: CORPSES DOWN THE OUBANGUI

The road from Fort Lamy was excellent tarmac through dense thickets of thorn bush for the first hundred miles to Goulengdeng, and then it was back to hard dirt, dust and corrugations. We passed endless little groups of four or five thatched conical huts, each group with a raised granary in the centre. In the late afternoon the hut dwellers worked in their bare fields, their backs bowed as they hacked at the hard, dried earth with a short adze. Both sexes, the old and the young, worked naked to the waist and they looked terribly sun-beaten and poor. Even so they all smiled and waved cheerfully enough as we passed them by.

As we neared Fort Archambault we became more apprehensive, fearing a sudden ambush, and the necessary wheel changes and breakdown repairs were accomplished with rapid speed with all non-workers keeping a constant watch. We felt very vulnerable with no weapons to defend ourselves except pangas and axes. However, either we were lucky or perhaps we were too large a party to be tempting bait, for on the third day after leaving Fort Lamy we arrived safely without so much as a glimpse of a rebel tribesman.

Fort Archambault proved no less expensive than the capital and so we passed through as promptly as possible and hurried to exit from Chad into the Central African Republic. Again it took several hours to get through the two sets of police and customs and to our dismay we found that still the war atmosphere continued. The CAR was having one of their usual domestic squabbles with their neighbours and had just thrown out the Congolese Ambassador to Bangui, their capital on the Oubangui River. The nature of the dispute was the most ironic and typically African yet, for the two countries had disagreed on the future shape of African unity. This was the pet subject of all the Pan African conferences at the time and they were almost prepared to go to war to settle their differences. For us the excitement and tensions generated by the issue meant more of those endless military roadblocks, being waved down by trigger-happy soldiers with rifles, and being forced to strip everything out of our vehicles while they turned it over. They were keenly interested in every item of our equipment and I began to feel that their enthusiasm was prompted more by boredom and curiosity than by any military devotion to duty.

The road was now a ribbon of red dirt leading south through a lush green landscape of rolling hills. The way was lined with endless scattered native huts with their little plots of maize and cassava. In the cool of the afternoon we took to riding on the swaying roof racks of the Land Rovers and waved like royalty to everyone we passed. They all ran out on to the road to wave back, everyone from the oldest greybeard granddad to the youngest pot-bellied toddler. Everyone had a big white grin. Darkest Africa, if you could ignore its politics, was all friendly white teeth and waving pink hands.

However, it wasn’t altogether possible to ignore the politics. Bokasso, the Army Colonel who had grabbed power in 1965, ran the country as a police state and some people compared him to Papa Doc of Haiti. He ruled from a large castle outside Bangui and despite the poverty of his people he managed to maintain his own jet aircraft. The airstrip at Bangui was the only one in the country capable of landing and launching the plane so the President used it solely for his own personal pleasure flips. There were dark rumours of torture and oppression taking place behind the castle walls and although the people of the CAR were friendly and pleased to give us a welcome, the officials were not.

Due to the checkpoints and delays it took us three more days to cover the three hundred miles to Bangui and at Yimbi, eight miles before the capital, we found that we had reached a frontier within a frontier. The road was barred with a steel barrier, with on one side the police and customs huts and on the other a magnificent tree that housed a vast colony of weaver birds. Thousands of suspended, ball-like grass nests gave it the appearance of some bizarre Christmas tree, or something out of science fiction infected by an alien growth. The birds were bright canary yellow with black faces and red crowns, and the combined effect of their massed fluttering wings was like a yellow snowstorm, mixed with a rain of primrose petals, falling and then defying gravity in a sweeping upward flight.

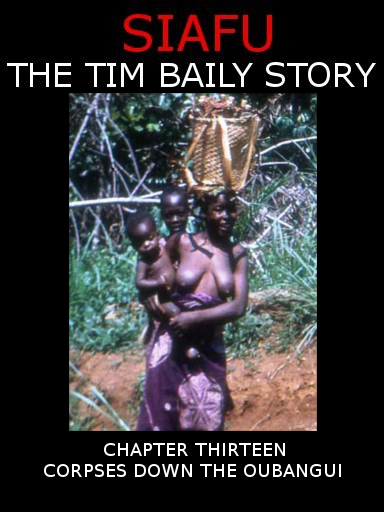

The cameras came out and then one girl spotted another photogenic scene. Beside the customs hut a young African woman was busily bathing her baby in a small tin bath. It was a perfectly natural picture and would have appealed to any young woman. Without thinking the camera was automatically raised and clicked again.

The response was frightening, for one of the customs officers in full uniform came running over in a fantastic rage. He grabbed the camera and broke it open to tear out the film. He was swearing furiously in French and our poor girl was too startled and upset to even try and answer in a language she didn’t understand.

A few of the fellows hurried over to try and help but the African official had a monumental chip on his shoulder. We had photographed his wife and child and in his view we only wanted these photographs to take home and show our friends what primitive and backward people the Africans were. This was the whole basis of his argument and he would not listen to any apology or appeasement. His wife bundled up her baby in embarrassment and hurried away and we quickly steered our amateur photographer out of sight. Both of them were near to tears.

Whether that incident had any bearing on what followed is hard to say, but it took us the best part of two days to get through that control post. All our passports were collected up, hours passed in answering questions and filling out lengthy entry forms, and when the passports were at last returned we found that there was one missing. I recounted them carefully, twenty-eight passports where there should have been twenty-nine. I told the African officials but they insisted that I had only given them twenty-eight. I insisted in turn that they had received all twenty-nine. They argued and refused to let any of us look inside their office. Finally they pretended to look themselves and only after that were we allowed to enter. Of course, we failed to find the missing passport. I argued and pleaded but all to no avail.

We finally drove into Bangui and camped on a piece of waste ground but we obviously could not continue until the “lost” passport was recovered. The next morning I paid a visit to the British Embassy but “Our Man in Bangui” wasn’t even English and proved a complete waste of time.

Fortunately, even though we were basically a British expedition, it was a French passport that had been stolen, and the French were better represented. They told us dubiously that it was very difficult to get anything done here, the police were the masters and talking to them when they were feeling bloody-minded was like talking to a brick wall. However, the embassy did send a diplomat to accompany us and we returned to the border.

We found a completely different shift of policemen on duty but although they were more reasonable they were equally unhelpful. There was no passport here, they said, and in any case the whole thing had happened yesterday and was nothing to do with them. Our friend from the embassy engaged them tactfully but without any results, and finally he risked the polite suggestion that we be allowed inside the office again to check for ourselves. The request was casually granted and once more we searched through the desk and looked around the shelves. We drew a blank, but at the last moment a young constable walked in, picked up his peaked cap which had been sitting on the desk-top, planted it on his head and calmly strolled out again. Where the cap had been the missing passport was at last revealed.

The other police officers were surprised! And they pretended to be pleased. All that we could do was to thank them politely and go on our way.

Bangui was just a small piece of grubby civilization that the French had forced upon Africa, but to us it was almost a metropolis. It had three sets of traffic lights, a handful of neon shop signs and a central roundabout where there was actually a small fountain playing. The town ended at the wide sweep of the Oubangi and on the far side of the river were the green jungle hills of the Congo. We relaxed for a few beers and were soon surrounded by flocks of hopeful Africans trying to sell us magnificent collections of tropical butterflies packaged up by the hundred in old shirt boxes. They had small boys out in the hills catching the butterflies at one cent each.

Our butterfly buying was interrupted when we learned that despite the troubles we had had at the city limits we were still expected to report to the central police station here in the city. It was the most lengthy process yet for all our passports had to be checked against the fat files listing all the people who had previously passed through and found disfavour with the Bokasso regime. There were long, three-page questionnaires to be filled in which demanded along with all the usual details our professions, salaries, and the names of our mothers and fathers and uncles and aunts.

I was soon horrified to find that some of my more exasperated expedition members were describing themselves as spies or Public Enemy Number One at five or six thousand pounds a year. One chap listed his parents as James Bond and Pussy Galore and after that I didn’t dare read any more of the papers.

Mercifully the African policemen couldn’t read English and all the forms were printed in French. The whole business took up most of the day but at last the officials were satisfied and we were released.

We spent another two days at Bangui, resting up while Allan and Andy fitted new brake shoes to “Henry” and “Maggie” and changed the leaking oil seals on “Matilda.” In the evenings we held parties and drank beer on the open veranda of the Rock Hotel that over-looked the star-lit river. Finally we left Bangui and back-tracked a hundred miles to Fort Sibut where we turned east again for a further three hundred and fifty miles to Bangassou. There we planned to cross the Oubangui into the Congo. The road was narrow, pot-holed dirt but fair by African standards. The main hazards were chickens and goats belonging to the native villagers. It would not have damaged a Land Rover to hit one, but every scrawny bird and animal probably represented a small fortune to its owner and so we felt obliged to take continuous evasive action.

Three days later at Bangassou we came to another grinding halt. We found the river there practically in a state of siege with a strong force of Central African troops dug in to fortified positions behind machine guns to face the Congolese garrison on the opposite bank. The military officials positively refused to let us cross and told us terrifying stories of the violent outbursts of shooting that came from the Congo every night, and of the limp corpses that drifted down the Oubangui with every dawn.

We had come too far now too accept defeat and once again I began the tedious round of tactful argument, polite pleading and constant assurance that we would accept full responsibility for our own fate. At least, I insisted, they could let us across to talk to the Congolese. They remained adamant, but finally conceded that if we could obtain a letter de passage from the higher authority in Bangui then the matter would be out of their hands.

There was no other choice but to make the one-thousand mile round trip back to Bangui. I took “Henry” and a couple of the men volunteered to come back with me and help out with the driving. Jan also insisted on returning with us, saying that no three men were capable of making their own tea and sandwiches so consequently we had to take a girl along.

We had a hasty supper and then set out to drive through the night. It was pitch black and the usual hazards of the jungle road seemed to flash up twice as fast in the lurching beam of the headlights. “Henry” skidded and swayed as I braked and swerved to avoid the ruts and pot-holes, and then roared as I accelerated to cover as much ground as possible before the next brake and skid. The overhanging jungle shut out the stars and the blackness was broken only by the faint glimmer of the fires beside the passing native huts. At intervals strange bright eyes shone back at us, never to be identified and left solely to our imaginations. We stopped shortly after midnight to brew up tea and could hear drums beating softly in the distance, a sound as familiar as the chirruping of the crickets, but the only thing that bothered us was the mosquitoes.

By taking it in turns to drive all through the night we reached Bangui by dawn. “Henry” had behaved magnificently without a single breakdown. I succeeded in getting the necessary letter which was issued with scarcely a shrug and piling back into the Land Rover we sped back to Bangassou. The road was familiar now although it was becoming more tiresome. With aching backs and shoulders we finally arrived back at the camp where we had left the bulk of the expedition.

In the face of the document from Bangui the military officers at Bangassou reluctantly washed their hands of us. If we crossed the river then whatever happened to us over there was on our own foolish heads they warned us gravely.

We thanked them and went down to the river bank. One obstacle was overcome but immediately we faced another. The Oubangui was at least three hundred yards wide and the ferry was moored on the Congolese side. The CAR soldiers shrugged and were not inclined to make any suggestions. We debated for a while and then prowled about looking for some means to cross other than by swimming. Then an African appeared on the far bank and began shouting and waving his hands to attract our attention. We watched him helplessly and at last he pushed out a canoe and paddled slowly toward us.

He was an old man who spoke neither English nor French and when he reached as he could only smile and sit there waiting in his canoe. He was obviously inviting one of us to step on board and be paddled across but now that the moment had come I was suddenly apprehensive. I remembered the shooting and the bodies.

The whole expedition was watching, plus the CAR soldiers. The old man in the canoe waited patiently, smiling and showing his brown-stained teeth. I looked at Allan Crook and Allan looked at me.

“We are supposed to be running this trip,” he said hesitantly. “So I suppose we ought to go across and find out the score.”

I nodded and put on a smile that I certainly wasn’t feeling as I stepped into the canoe and sat down. Allan got in behind me, also smiling dubiously, and then the old African began to paddle us back toward the Congo.

I tried not to think about the bristling array of machine guns that were pointing at us from both banks.

ROBERT LEADER

ROBERT LEADER

Write a comment

Do My Paper For Me (Thursday, 22 June 2017 13:19)

The focal point has a outrageously rewarding ride. It felt fixed, firm, and really damn enjoyable. On permeable streets, or more deplorable, the edge appear to hose the most noticeably awful vibrations, and secured the bars from humming. That is infrequent on a cycle this light.

dissertation proposal writing service (Saturday, 17 November 2018 12:41)

This is really very nice post you shared, I like the post, thanks for sharing..